Sport

Dollar

38,2552

0.34 %Euro

43,8333

0.15 %Gram Gold

4.076,2000

0.31 %Quarter Gold

6.772,5700

0.78 %Silver

39,9100

0.36 %The shocking difference between African and European football might explain why many young African players would not mind doing anything to escape the misery of their profession in their own countries, regardless of the possible success or failure.

By Omar Abdel-Razek

The 2023 AFCON is the biggest festival for African football. For millions of fans across the continent, it’s not only an occasion to support their national teams but also a time to watch the contributions of their iconic national players who left their local teams for the limelight of European clubs.

Players like Senegal’s Sadio Mané and Egypt’s Mohamed Salah are striking examples of the victories and ironies of African football. Do they represent the “globalised” African football or the “muscle-drained” talents?

While football is the most popular game in Africa, its development in recent decades has been far less than this popularity suggests. Lack of investment, corruption, and the “muscle drain” of the best talents have clearly contributed to this current situation.

Many commentators can’t resist the temptation of comparing African football to the European one: why is the game declining in Africa while becoming an important source of employment, investment, and GDP in Europe?

Both African and European football associations have nearly the same age. The Union of European Football Association (UEFA) was established in 1954 and has 55 national associations under its umbrella at present.

The Confederation of African Football (CAF) was established in 1957, with the first championship in Khartoum between Sudan, Ethiopia, and Egypt after South Africa’s withdrawal due to its refusal to participate with a mixed-race team.

With 54 countries in its membership, the CAF announced in 2023 that its revenues reached a record $125.2 million.

On the other hand, the annual Deloitte report for football finances revealed that the value of the European football market reached €29.5 billion in 2022, with the big five European leagues generating a record revenue of €17.2 billion.

This shocking comparison between two worlds of football might explain why many young African players would not mind doing anything to escape the misery of their profession in their own countries, regardless of the possible success or failure.

According to many reports, there are more than 500 African footballers in the European leagues, representing more than 35% of the foreign players in these top teams.

Many may argue that those players have made history for their countries and become role models for children and youth alike, aspiring for fame and wealth. Nobody can deny the effect of Mo Salah, for example, in advancing the values of multicultural and interfaith society in Britain.

When Liverpool’s fans chant “Mohamed Salah, a gift from Allah” combined with extensive media coverage of the exemplary manners of the Egyptian Muslim “pharaoh king”, the situation reinforces the assumption that celebrity footballers like Salah can change the world around them.

According to a 2021 Stanford University study, Salah's performance with Liverpool and his showcasing of his Islamic faith without scrutiny, has changed the perception of Liverpool fans towards Islam and Muslims.

A similar argument defending the movement of African footballers to Europe will consider it as part of the increasing policies of globalisation. In a globalised economy, football and players are not just a game, they are a commodity and must correspond to the rules of the market.

“Muscle Drain”

While the migration of labour, skilled and unskilled, from the periphery and semi-periphery countries (Africa, Asia, and Latin America) to the industrial core of the world economic system is not new (it became widespread after the second world war from the colonies to the colonial centres in Europe), the exodus of talented footballers is relatively new.

In the early years of the 1990s, European clubs eased the restrictions on the number of foreign players in their teams after the European Court of Justice ruling in 1995 (Bosman Ruling) reversed FIFA regulations about the transfer of foreign players, their numbers in official matches, or paying transfer fees for players out of contract with their original clubs.

After this ruling, “it became more difficult for African clubs to retain their best players in the face of enticing offers from European clubs, consequently reducing them to the status of talent-exporting clubs,” according to Iwebunor Okwechime and Olumide A. Adetiloye in a study published in 2019.

This trend paved the way for European clubs to establish networks for the “search and pull” of African football talents to join their teams.

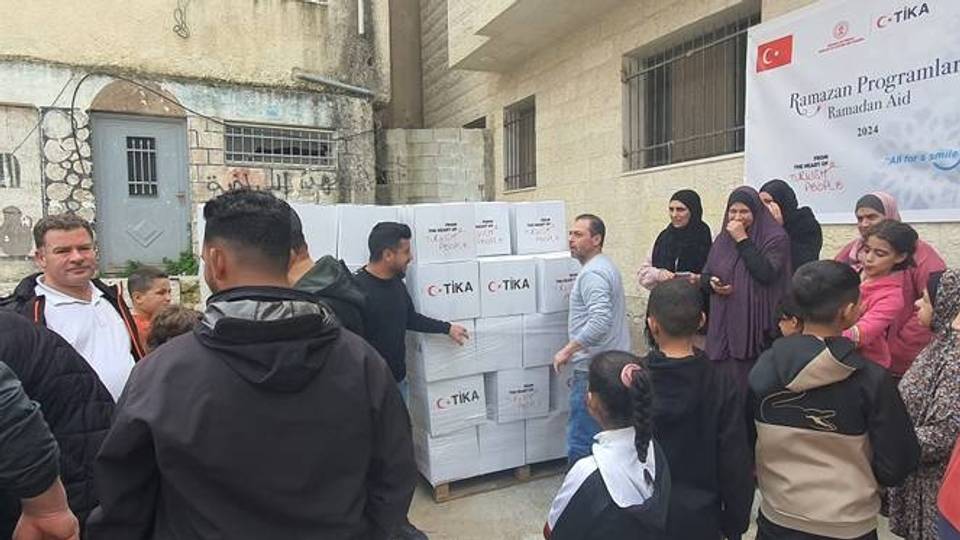

These networks include recruiters, agents, tipsters, and football academies, most of which are not subject to rigorous regulations in Africa and are benefiting from corruption in the sports sector.

Structural Defects

It's noteworthy here that the peak of footballer’s migration to Europe came in a turbulent period for most African countries.

The 1990s was the period when most African countries were forced to implement the neoliberal economic reforms set by international financial institutions, which meant that sectors like sports and culture became a luxury for most African governments, prompting talented players and others to seek greener pastures in Europe.

This negligence, combined with corruption and nepotism, has contributed heavily to the current situation of African football.

Most African clubs are run by governments, with limited financial resources, a lack of pitches, training, or regulated academies to polish football talents. Some players complain they don’t receive their wages for months.

Recruiting players for local clubs doesn’t follow transparent rules but follows decisions made by the agents of the players and how much they pay to the officials. In recent years, European leagues have recorded more viewership in the continent than the local ones.

The number of spectators in African leagues is declining continuously, depriving local clubs from the very important source of income their European counterparts enjoy.

Despite the global presence of African players, African football struggles to match the standards set by European or Latin American leagues. With few exceptions, such as South Africa and Egypt, African football lacks a professional framework, perpetuating the "muscle drain" it contends with.

Addressing these structural issues becomes paramount for the continent's football to thrive on the international stage.

The imposing presence of African footballers on the international stage contradicts the declining state of the game at the local level. With few exceptions, such as South Africa and Egypt, most African clubs are underfunded with insufficient pitches and poor training facilities.

African football lacks a professional framework that can elevate it to the standards seen in Europe or Latin America. If these challenges remain unresolved, Africa might not be able to fulfil its hope of increasing its representation from 5 to 9 teams in the next World Cup 2026, and the issue of “muscle drain” will persist.

The author, Omar Abdel-Razek, is a Sociologist and Former Editor at BBC Arabic. He lives and works in London.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of TRT Afrika.

➤Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel for more stories.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment