Sport

Dollar

38,2552

0.34 %Euro

43,8333

0.15 %Gram Gold

4.076,2000

0.31 %Quarter Gold

6.772,5700

0.78 %Silver

39,9100

0.36 %After receiving life-changing medical care abroad, some Palestinian children have said they are determined to rebuild their lives and inspire others.

By Indlieb Farazi Saber

Over a game of cards, 12-year-old Hadi Zaqout once again beats Randah Zalatimo in a straight-faced game of Trump, where the player holding the highest card in the suit wins the round.

"Raqzi khalto, raqzi," Hadi quips in Arabic while smiling at Zalatimo, which means "focus aunty, focus," insisting if she only paid more attention, she may pick up some skills and win the card game.

"He always cheats, but with a giggle and a smile he gets away with it," says Zalatimo from her home in St Louis, Missouri, where Hadi now spends his weekends, playing with his aunt, a volunteer for Heal Palestine and her 13-year-old son Haider.

Hadi is from Mawasi, just west of Khan Younis in southern Gaza. He arrived in the United States with his mother Camille Zaqout in May for medical treatment, after he lost his right leg in an Israeli air strike last November.

"Doctors in the US complimented my amputation saying it was done perfectly, and I said of course, in Gaza the doctors have had to become experts in this," the boy told TRT World.

Limited assistance abroad

Hadi is part of a group of 22 children evacuated from Gaza to Egypt before arriving in the United States over the course of the year.

Due to border closures and rigid documentation checks, most amputees from this war cannot leave Gaza for medical treatment abroad.

As of September 12, the United Nations states Israeli authorities have only allowed 219 patients to exit Gaza since the closure of the Rafah border crossing in May 2024.

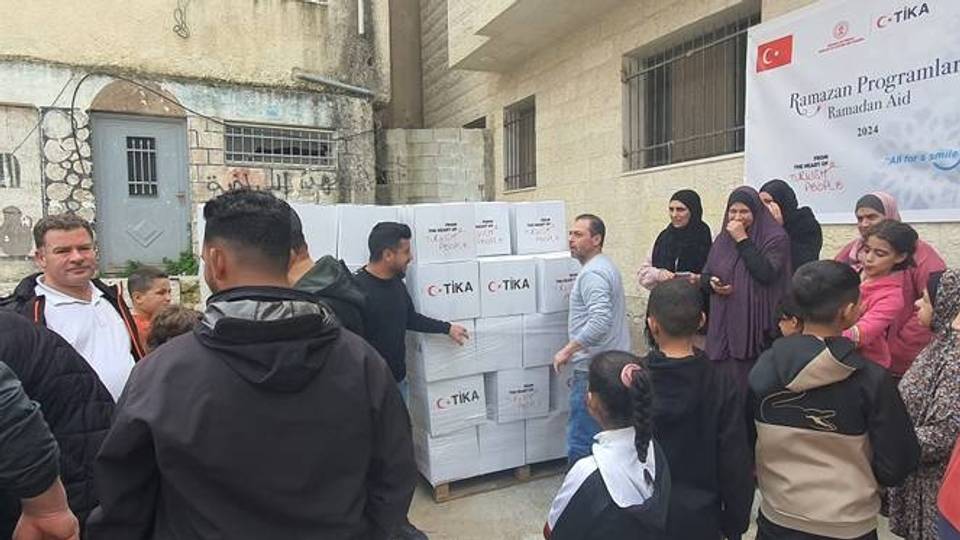

Prior to that, of the 14,000 patients for whom medical evacuation has been requested since October 2023, just over 5,000 have been evacuated. Host countries include Türkiye, Qatar and South Africa. In the US, Heal Palestine has been able to grant medical evacuation visas to the children, on the condition they cannot apply for asylum, and must leave the country once their treatment is complete.

The day it all changed

The only son in a family of five sisters, Hadi has always had a sense of duty for his family, which only became heightened during the war.

He was the one who would go in search of daily water when it became in scarce supply early on in the conflict.

Queuing in line for hours to make sure his parents and sisters would have clean water to drink became his daily mission, until one morning on November 11, when he discovered a way to access a different water source from a pipe within his apartment block.

The Zaqouts lived on the fourth floor, and as he walked in through the front door to proudly show his family his hack for getting water, there was a loud explosion and everything turned dark.

"I opened my eyes and there was just rubble everywhere. I didn't feel anything. I didn't feel pain. I was still in shock, looking around me, I couldn't see anything. There was just a lot of dust and rubble," Hadi said.

His family survived the blast, but apart from his mother who found him in the hospital days after his amputation, he hasn't seen his father or sisters since that day.

Hadi was found by rescue workers trapped under the rubble hours after the explosion and put into a vehicle to be taken to the local hospital. Beside him, he recognised the lifeless bodies of two friends from his block, Mohammed and Tayyab.

"I'm never going to forget that scene. I didn't think of what's happening with me. I didn't feel anything. I just knew that there was a lot of blood everywhere and I'm just looking at these two boys thinking, 'what happened?' We were just standing there getting water."

At the Nasser Medical Centre in Khan Younis, where Hadi received medical care and where his mother would later find him, doctors treated his right arm and his left leg which were both severely injured in the strike.

But within two days, his leg became at risk of infection and he was told it would have to be amputated.

"The hospital said the injuries that they are seeing from the bombs the Israelis are using have some kind of chemical that causes an infection that spreads across the body," Hadi's aunt explained.

Early in the war, Palestinian Ministry of Health in Gaza stated Israel was using “unusual weapons” that cause severe burns to the bodies of victims. It was a claim later backed up by visiting international doctors.

A brave Hadi said the first thing that crossed his mind was his family, who are now displaced in a tent in Khan Younis.

"I was thinking that I'm the man of the family after my dad and they need me to be there throughout my life and I need to be there. So I need to stand up and do this. Everyone needs me."

Doctors amputated his leg, but his arm required further medical treatment that they weren't able to provide, due to limited supplies of medicine and dealing with many other patients' complex injuries.

One of thousands

Hadi is one of the "lucky" ones as he was operated on with anaesthesia. But due to dwindling medical supplies and a decimated health system caused by Israel's assault, thousands more have been operated on without it.

In June, head of the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) Philippe Lazzarini estimated more than 2,000 child amputees had been created from this war, described by Dr Ghassan Abu-Sittah, a leading British-Palestinian surgeon, as the largest cohort of child amputees in history.

But that figure could be much higher a year into the war, with thousands more children missing and unaccounted for.

Dr Abu-Sittah, also author of The War Injured Child, spent 43 days in Gaza earlier in the war, conducting emergency surgeries with Doctors Without Borders (MSF), at one point performing as many as six amputations a day.

Speaking to TRT World, he said child amputees in particular need lifelong care, as he works to keep a record of all the children he's treated through his consultancy work at the Centre for Blast Injury Studies at Imperial College London and the Global Health Institute at the American University of Beirut.

"Because a child is still growing, they will need a new prosthetic or at least have their prosthesis adjusted, every six months. Depending on their age, they may need between eight to 12 surgeries by the time they're adults," he said.

He added that an MSF study in Gaza found 40 percent of amputees couldn't wear prosthesis at some point because of complications with the stump site.

From a medical perspective, amputees often also experience post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety as they try to recover from their injury. But the children interviewed for this piece displayed an unmatched resolve which ties into the resilience shown by Palestinians who continue to defy their attempted destruction.

"I don't think it actually dawned on him what's happened to him," says Zalatimo. "Deep inside, you feel that there's pain and there is frustration and there's anger. You know he's just 12 years old. An adult can't deal with this, let alone a 12-year-old."

'We get more'

"Whatever they get out of this, we get back even more," says Dr Fiona Tagari, another volunteer from Heal Palestine, a non-profit organisation run by volunteers that's offered safe spaces for children to rehabilitate physically, mentally and socially.

They are also provided with an education to make up for the paused academic learning Palestinian children are facing since the start of the massacre.

Tagari and her family have been hosting 14-year-old Mohammed Abou Samour and his mother Sabrine at their home in Houston, Texas since August.

The youngest of eight children, born into a family of farmers, Mohammed spent much of his day outdoors, often playing football.

It was in May while he was displaced with his family on the outskirts of Khan Younis that he discovered a metal object just outside the tent. The object, likely an IED, detonated while he was holding it, causing him to lose his left hand and part of his left arm, three fingers on his right hand and both his legs.

After three surgeries and an eight-week stay at Gaza's European Hospital, Mohammed’s case was considered critical and he too was taken to Egypt for further treatment.

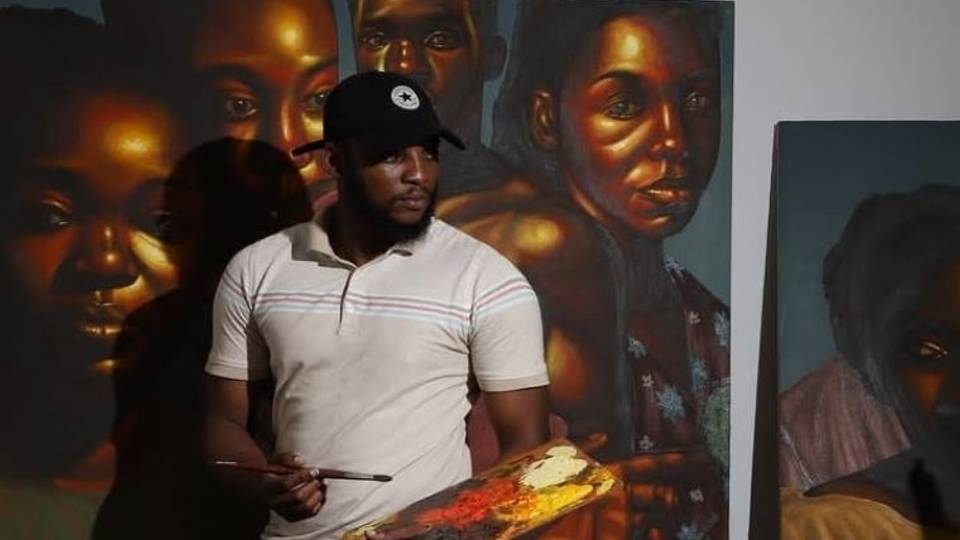

"When he arrived to us here in Texas in August, Mohammed didn't want to look at his hand with only two remaining fingers, but now he's using that hand to paint, and even feed himself. Knowing he'll get his prosthetics once the graft site on his leg has healed has lifted his spirits," Tagari said.

He has also started to transfer himself from his bed to the wheelchair, and the wheelchair to the car seat, because he's motivated to help himself, she added.

Mohammed says what he wants most is to "return home to Gaza, to play football and to one day become an artist," but he is still in the early days of his treatment, which will last for months more.

Meanwhile, Hadi’s medical care in the US is coming to an end. Now able to walk with one crutch and use his right hand, he'll soon be getting a third prosthesis fitted on his leg, then travelling to Cairo where he'll have the chance to continue his education.

The affable boy had once wanted to become a footballer, like his favourite player Liverpool's Mohammed Salah, but that all changed after meeting fellow amputee Dr Darren Rottman while being treated at the Shriner's Children's hospital in St Louis. Hadi now said he's hoping to also become a doctor.

"I need to go back one day and help the kids to show them there is hope. I was the fortunate one to get help, but there are still thousands more," he explained.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment