Sport

Dollar

38,1477

0.31 %Euro

43,7114

0.14 %Gram Gold

4.078,2400

0.36 %Quarter Gold

6.720,2300

0 %Silver

39,9300

0.41 %Chadians are rallying behind their government amid a reimagining of relations with erstwhile coloniser France, reflected in the remembrance of horrors perpetrated by the colonial forces over a century ago.

By Tuğrul Oğuzhan Yılmaz

Some wounds don't heal, festering and gnawing like the pain of past injustices.

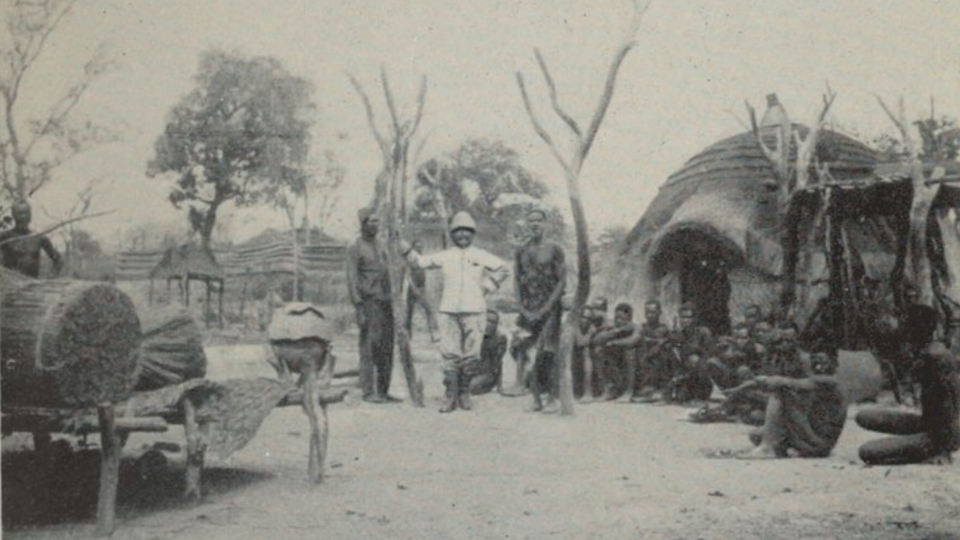

Nowhere is this truer than in Chad, where the scars of French colonialism are etched in the collective memory of a generation that lived through the horrors of one of the worst episodes of oppression — the infamous Coupe-Coupe Massacre of November 15, 1917, in the town of Abéché.

"Chad for us, France out!" This chorus of angst is reverberating through the Central African nation, reflecting the groundswell of opinion that has seen France's military presence in Africa decline significantly in recent years.

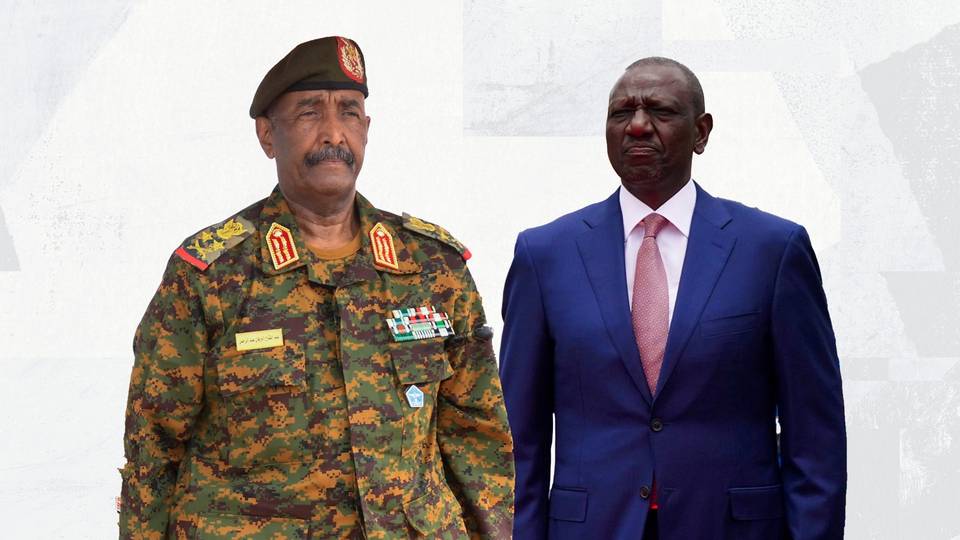

On November 29, the Chadian ministry of foreign affairs announced the cancellation of its security and defence industry cooperation agreement with France, coinciding with the visit of French foreign minister Jean-Noël Barrot and his meeting with President Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno a day earlier.

While France expectedly responded cautiously to the annulment of the September 5, 2019 pact, Chad emphasised its sovereign right to its territory.

Soon after, protests erupted across the country against French military presence.

Beginning December 5, these demonstrations quickly spread to major cities, including N'Djamena and Abéché.

Just ten days earlier, a Friday sermon in Abéché marked what would be the turning point in the outpouring of anti-French sentiments on the streets of Chad.

On December 6, Chadians who had gathered for prayer were again galvanised into introspecting on that painful moment inflicted by the French on their region's history 107 years ago.

So, how did the tragedy of the Coupe-Coupe Massacre play out in Chad's bloody history of French colonialism, and what does it mean to its people?

Journalist and author Kamal Koulamallah from the Chadian media organisation Le N'djam Post describes the 1917 massacre that took place in Abéché, the capital of Wadai, as "an indelible stain on Chad's history".

"A brutal crackdown that will forever leave its mark on local memory. Between unfounded suspicions, methodical reprisals and colonial policies of impunity, this dark page of the French colonial presence in Chad has spanned the century to remain, even silently, a symbol of injustice and suffering," he explains.

Merchants of tyranny

France intensified its colonial activities in Africa in the 19th century, with Chad being among the countries targeted for domination.

From the late 1800s, the country was effectively divided between British and French spheres of influence. "Before Western colonialism set foot on the continent, three local sultanates ruled in Chad: the Wadai, Bagirmi, and Kanem Sultanates.

These states fought fiercely against the French for many years and maintained good relations with the Ottoman Empire.

This relationship was similar to today's Türkiye-Chad ties," Dr Isa Gökgedik, a member of Türkiye Kütahya Dumlupınar University's faculty of theology, tells TRT Afrika.

The French first entered Chad in 1899, establishing dominance in N'Djamena, which they referred to as "Fort-Lamy".

They then sought to expand their colonial administration to regions such as Abéché, Wadai, Borkou, and Ennedi. Beginning in 1905, they encountered resistance from the Arabs, Tuaregs, Uled Slimans, and the Libya-based Sanussi forces supported by the Ottoman Empire.

After a decade of fighting, French forces led by Col. Moll and Dr Chaopen occupied Abéché on August 23, 1909.

During this period, Wadai Sultan Mohammed Salih (Dud Murra) and Dar Masalit Sultan Tajuddin allied to launch a resistance.

Tribes such as the Abu Sharib, Havalis, Kelingen, Kodoy, Mimi, Veled Cema and Maba, along with the Ottoman-backed Sanussi forces, joined the fight, refusing to accept French occupation.

Col. Moll was killed in battle, as did Sultan Tajuddin. Sultan Muhammad Salih and Tajuddin's nephew, Bahruddin, continued the resistance for a while but were forced to surrender on October 27, 1911.

Col Victor-Emmanuel Largeau captured Ain Galaka, Bilma, and Biltine between 1912 and 1914. The aftermath of these assaults, coupled with famine and epidemics, led to 322,000 people dying in Abéché alone.

The population plummeted from 728,000 to 406,000 within three years.

Trial by mass murder

The staggering figures clearly illustrate the extent of the depredations orchestrated by the French.

During World War I, hundreds of thousands of Africans were forcibly recruited under the false promise of independence and sent to die on European battlefields against the Germans.

Despite the ongoing war, the French struggled to establish complete control over Chad.

To break the resistance, they devised a systematic plan to eliminate respected religious scholars in the community through massacres.

Unashamed to resort to deception, the French invited community leaders to Abéché in 1917 on the pretext of consulting them on governance matters.

At dawn, following morning prayers, hundreds of Muslim scholars were ambushed and killed. Similar massacres were carried out in Varya and Kanim.

The Coupe-Coupe or "Cut-Cut" Massacre wasn't just an act of unrestrained savagery by the French soldiers, who beheaded several Chadian Islamic scholars with machetes.

The colonial forces also confiscated books and manuscripts from libraries, either burning them, sending them to museums in France, or hiding them in underground storage facilities.

A vast cultural heritage was obliterated in the mayhem.

Yahya Ould Germa, who opposed the forced conscription, was imprisoned. Akid Magine and his wife, Meram Koise, faced intense pressure.

Akid Mahamat Dokom, who refused an alliance with the French, was killed with a hundred of his supporters.

Abud Sharara, leader of the Mehamid tribe, was arrested with 40 of his followers and later executed.

To suppress potential uprisings, the colonialists deployed troops from European fronts to Chad, implementing harsh security measures.

They also targeted the people’s spiritual values to provoke and subjugate them.

The Great Mosque was demolished, and protests in the Salamet and Batha regions were violently suppressed.

During this period, waves of arrests, exiles, and assassinations followed one another.

Even the slightest human reaction was brutally silenced.

Despite this, the people of Chad never accepted colonial rule, and their resistance continued until the 1930s.

After decades of oppression, Chad gained independence from France on August 11, 1960.

Quest for retribution

The Coupe-Coupe Massacre remains a highly sensitive subject for the people of Chad to this day.

The fact that the French are still to apologise for what they did to the region and its people makes it worse.

"Some intellectuals want to move the International Court of Justice against France, which tells you about the hatred any mention of the massacre in the Wadai region invokes. Conferences have been organised, and many young people are well informed about the massacre," Dr Mahamat Adoum Doutoum, who teaches history at Cheikh Adam Barka University in Abéché, tells TRT Afrika.

"The death toll in the Coupe-Coupe Massacre is estimated to be 150. More than the number, the brutality and intent of the attack heightens the sense of injustice."

The scholars murdered by the French were buried in a mass grave at Umm Kamil in Abéché.

The cemetery has since become a monument to martyrdom, symbolising the Chadian people’s struggle for independence against the occupiers.

"The Coupe-Coupe Massacre is an emotive rallying point for Chadians against the French.

Harking back to it instantly creates unanimity among the population, be it seeing colonialism for what it was or garnering support for the government's decision to end its security and defence cooperation agreement with France," explains Dr Doutoum.

"Only a small minority hasn't expressed their support for this decision. Although they remain silent, that has little influence in the face of a larger consensus."

On the anniversary of the Coupe-Coupe Massacre a month ago, Chadians across the social spectrum vowed never to forget what the French did to their country and people. "France out!" – the cry couldn't be shriller in this time of flux.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment