Sport

Dollar

38,2552

0.34 %Euro

43,8333

0.15 %Gram Gold

4.076,2000

0.31 %Quarter Gold

6.772,5700

0.78 %Silver

39,9100

0.36 %A UNDP study of sovereign credit ratings across African economies reveals that so-called 'subjectivities' in the processes followed by S&P, Moody's and Fitch cost the continent about US $74.5 billion in excess interest and missed funding.

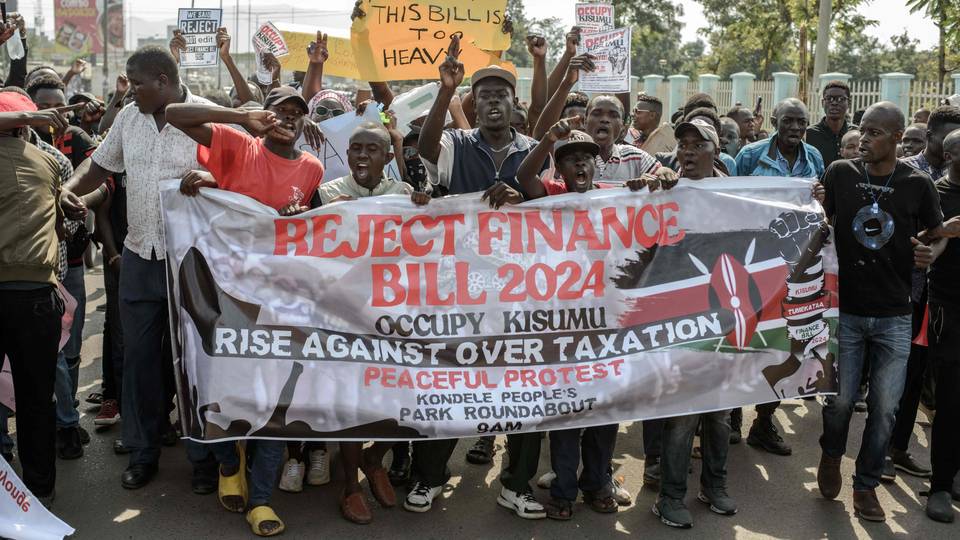

The storm of public unrest uncorked by the Kenya Finance Bill 2024 may have blown over, but it has left in its trail an uneasy calm for the East African nation to deal with.

The decision by President William Ruto's government to bow to the anti-tax protesters has caused the Big Three of global credit rating agencies to downgrade Kenya from B to B-.

The latest downgrade came from S&P on August 23, pushing it further into what the credit market calls "junk" territory.

"The downgrade reflects our view that Kenya's medium-term fiscal and debt outlook will deteriorate following the government's decision to rescind all tax measures proposed under the 2024/2025 Finance Bill," the US ratings agency said.

Raymond Gilpin, chief economist for Africa at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), notes that the impact of the credit downgrades will be felt not just by the government's kitty but also the ordinary citizen's wallet.

"The quantum of interest Kenya pays on its debt will likely increase. Those who lend to the country will obviously see it as a riskier proposition and, consequently, interest rates on bonds or loans that aren't fixed could go up," he tells TRT Afrika.

When interest rates spike, it more often than not results in a domino effect, including a sharp increase in the cost of goods and services.

Economists are even more worried that the increased cost of debt could reduce the size of the government's corpus for investment in job creation and social sectors like healthcare and education.

"Data shows that 750 million Africans live in countries paying more on debt servicing than what they invest in health and education," says Gilpin.

How countries are scored

Investors and debt issuers rely on credit rating agencies for information about the risks and opportunities associated with a sovereign borrower.

Credit scores become especially important when an external investor is unfamiliar with a specific country's context, which is usually true in emerging and developing markets.

UNDP highlights that the sovereign credit ratings assigned by S&P, Moody's and Fitch are critical in enabling emerging and developing economies to secure sufficient funding to achieve their development goals.

"These opinions are the outcome of looking at macroeconomic, institutional and governance data on a specific country and seeking credit feedback from institutions and individuals working in or with the country," explains Gilpin.

So, doesn't such a system amount to creating room for manipulation or undue influence?

UNDP recently analysed sovereign credit ratings across African economies to check for bias and reviewed the link between ratings and the development process.

The study ruled out bias in Africa's credit scores because of the similar methodology being applied worldwide, although it revealed "subjectivities" in the approaches taken by the three major rating agencies.

Costly subjectivities

UNDP's findings show that developing economies have been significantly impacted by the recent sharp downgrades of their credit ratings, resulting in higher borrowing costs and increased debt sustainability risks.

About 95% of the downgrades have occurred in developing countries, which UNDP acknowledges has negatively affected their ability to raise new capital and maintain established commitments.

The study established that to arrive at a fair conclusion, credit rating agencies require significant amounts of data and capacity, which they lack while working in many African countries.

"If they don't have the data, they have to make subjective judgments," says Gilpin.

"When we at UNDP studied 19 African countries to see what this subjectivity cost, it came to $74 billion. That's more than what the entire African continent receives in aid every year."

This equates to 80% of Africa’s annual infrastructure investment needs, estimated at $93 billion.

The US $74.5 billion cost is a combination of excess interest charged on loans and funding that these 19 countries have foregone.

This is just the tip of the iceberg, given that the study did not cover more than 30 countries on the continent.

"These are subjectivities that we can fix, and we must fix," says Gilpin. "We have a responsibility to safeguard our economic future."

UNDP is working with several other agencies to enhance research capacity in African countries to ensure that their credit rating processes are much more objective and not based on opinions from writers who don't live on the continent.

Gilpin insists that disclosure is paramount. "If a country is being downgraded because of X or Y, the country needs to know so that they could work on it," he says.

Opportunity to reset

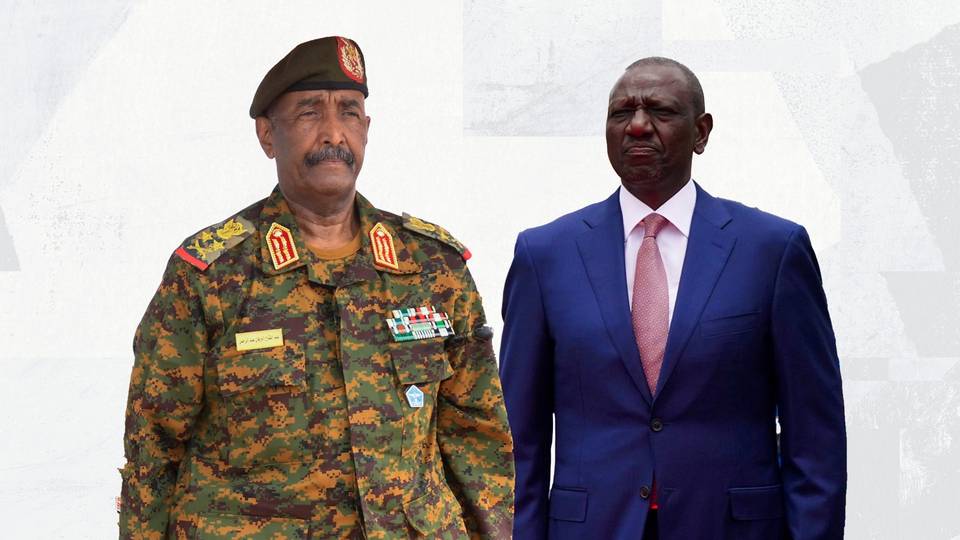

In Kenya, President Ruto's administration is still grappling with the country's $78 billion debt, with the finance minister indicating earlier this month the government plans to raise about $1.2 billion by reinstating some unpopular taxes.

While the economy could take a further hit due to the recent credit downgrades, Gilpin sees a silver lining.

“A downgrade could suggest that the cost and volume of investments will suffer, but I also see it as an opportunity to reset. It's a good thing that the Kenyan government is taking a new look at the finance bill — seeing what could be postponed and cut off to balance the budget," he explains.

“This is not a time for despair. It's a time to fix the structural imbalances in the Kenyan economy."

S&P reckons Kenya's outlook is "stable" despite the downgrade, citing expected "strong economic growth and continued access to concessional external financing".

➤ Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel for more stories.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment