Sport

Dollar

38,2552

0.34 %Euro

43,8333

0.15 %Gram Gold

4.076,2000

0.31 %Quarter Gold

6.772,5700

0.78 %Silver

39,9100

0.36 %The spread of Mpox and persistent imbalances in vaccination within Africa portend the start of another potential pandemic unless the US and other developed countries look beyond their own needs.

By Susan Mwongeli

The nomenclatural journey of a new virus isn't just about science unravelling its sinister secrets.

As the last global pandemic transitioned from "Novel coronavirus" to "2019-nCoV" to "Covid-19" to a menagerie of strains — Delta, Alpha, Omicron and more — countries trying to stave off the march of the virus quickly learnt that an interconnected world has no oasis.

Wuhan is just a whisper away from everywhere else. Amid a fresh Mpox outbreak driven by a mutated strain known as Clade I, the truth is out there.

This isn't just a threat restricted to one continent. This is another potentially deadly worldwide public health emergency.

The Clade 1 outbreak started in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2023, with thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths being confirmed since.

Mpox continues to spread in Africa and beyond. On August 13, the Africa Centres for Disease Control (Africa CDC) declared Mpox a "public health emergency of continental security".

More than a month later, several countries outside the continent have started reporting this highly infectious zoonotic disease with symptoms similar to that of smallpox.

Apart from the DRC, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, and Morocco have had cases of Mpox, including fatalities.

Mpox has also been reported in Sweden, the Philippines, Thailand, Pakistan, and India.

"This is not just an African issue. Mpox is a global threat, a menace that knows no boundaries, no race, no creed," says Dr Jean Kaseya, director general of Africa CDC.

Periodic outbreaks

Mpox was first discovered in colonies of monkeys kept for research in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1958.

The first human case was detected in 1970 in Congo. Since then, there have been periodic outbreaks worldwide, particularly in West and Central Africa.

The current one is potentially the most damaging in terms of spread and impact.

Lukanga Bugala, a resident of Goma in eastern DRC, didn't suspect anything was amiss when he spotted what he thought was "a simple pimple" on an eyelid.

"I put some medicine on it, believing it would heal. But more pimples started sprouting, and I decided to visit a hospital, where I was told that this was a viral illness," he tells TRT Afrika.

Mpox spreads through skin-to-skin contact with an infected person or animal, sometimes even surfaces they may have touched. Experts say rodents are carriers of the virus, too.

"Mpox is essentially a neglected tropical disease. It's looked at as a disease primarily affecting people in Africa," says Dr Sharmila Shetty, vaccines medical advisor for the MSF Access Campaign.

Generally, patients with robust immune systems and those without prior skin disease recover quicker with supportive care and pain-relieving drugs.

Those at higher risk of severe infection include people with severely weakened immune systems, infants, those with a history of eczema, and pregnant women. Healthcare workers are also at higher risk of exposure to the virus.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), gay people are also at high risk of Mpox, which typically manifests itself with a rash, fever, sore throat, headache, and muscle aches.

Other symptoms include back pain, low energy, swollen lymph nodes and skin lesions.

Stronger strain

Among the two virus strains, Clade I and II, the first is more severe and has a higher mortality rate.

"It's clear that a coordinated international response is needed to stop these outbreaks and save lives," WHO's director general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, says of the surge of the new variant.

In 2022, WHO had designated Mpox a global health emergency amid rising cases of the Clade II strain.

The alert was withdrawn in May 2023 after infections declined, only for Africa to report a new outbreak. Many experts say ending the emergency was a premature decision.

DRC, which remains the epicentre of the virus, has been rendered more vulnerable by years of armed conflicts and mass displacement.

This year alone, the country has recorded more than 27,000 suspected Mpox cases and 1,300-odd deaths. Children under the age of 10 account for the most infections.

Vaccination gaps

Dr Angelique Coetzee, former chairperson of the South African Medical Association, says not being vaccinated against smallpox makes kids susceptible to Mpox.

"We know that since 1980, hardly any vaccination has been carried out. In Africa, many young people generally fall sick because they do not have resistance to viruses as older people who have been vaccinated against smallpox," she tells TRT Afrika.

DRC and other African countries are struggling to get sufficient Mpox vaccines.

"There is an urgent need for vaccines to halt the transmission chain," says Dr Shetty.

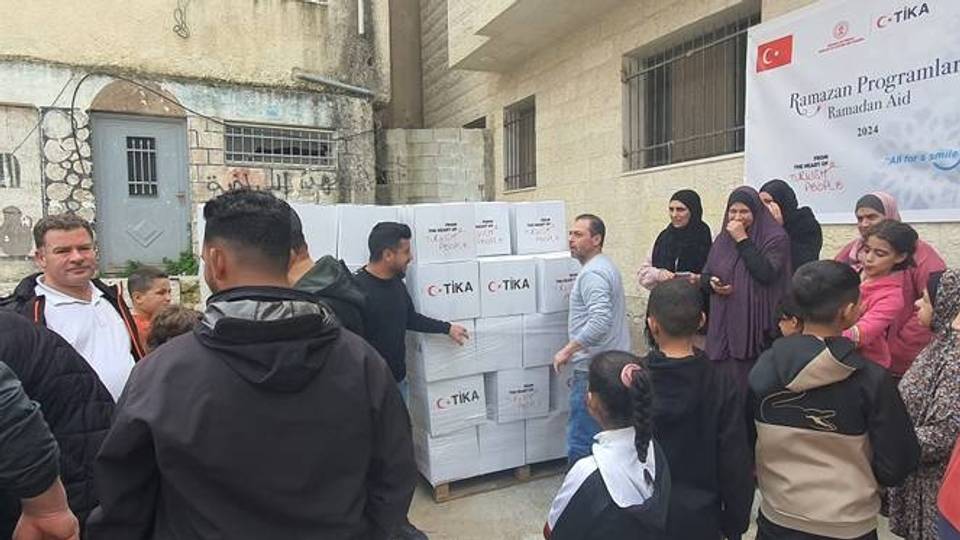

On September 5, the DRC received its first batch of 99,000 doses of Mpox vaccines from the European Union and another 50,000 doses from the US days later.

However, these numbers are far short of the three million doses officials estimate are needed to bring the outbreak in the DRC under control.

The vaccine delivery came nearly two years after the US and some European nations began stockpiling doses for their populations to pre-empt outbreaks.

“We know that the shortage of vaccines is quite high in the African context, and no one cares about it. We saw the same with Covid-19. The Western countries are now hoarding these vaccines to try to protect their people if they are infected with Mpox," rues Dr Coetzee.

In many ways, the current situation mirrors what African countries faced at the height of the pandemic in 2020, particularly the late and restrictive access to vaccines.

"We are where we were then. And these vaccines are quite expensive, around US $100 a shot," says Dr Coetzee.

WHO data shows that Africa imports 99% of vaccines required to tackle various diseases.

Only five countries on the continent – Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa and Tunisia —have facilities to produce vaccines. Many are reliant on donations or donor-driven international initiatives for their vaccine requirements.

Dependency problem

Dr Dimie Ogoina, an infectious diseases expert in Nigeria who chairs WHO's Mpox emergency committee, highlights the imbalance.

"We are still working blindly in Africa; we don't have the required knowledge about Mpox's natural history, transmission dynamics, risk factors," he explains.

"Essentially, you need to understand your context and your disease for you to develop or design preventive strategies."

For now, Denmark-headquartered biotechnology company Bavarian Nordic is retooling certain vaccine supply pacts to ensure its vaccines go to the regions that need them the most.

"They are planning on discussing with some African manufacturers to transfer the technology to them, which is a welcome step. But what we also need to see is not just sort of the end point of the manufacturing process," says Dr Shetty.

➤Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel for more stories.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment